Visual art editorial

by Patricia Coleman

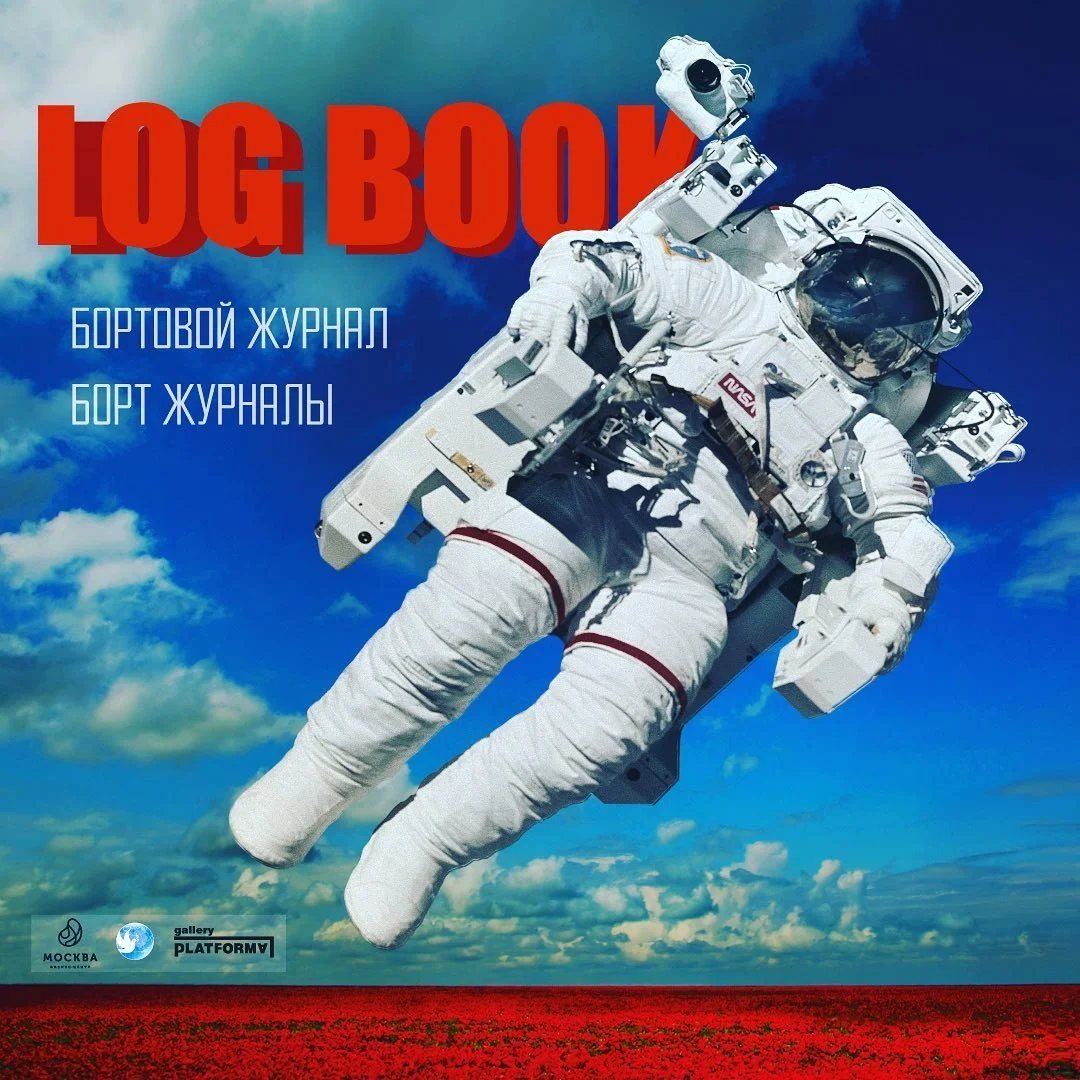

From the cosmos, the earth may resemble swirling detritus; zeroed in on, individuals can be observed burning the dross in their own mundane variations of one another. Corbin Louis’s “Brand New [Empire] Teaser” leads the reader’s gaze/ear into America-as-film/poem: jump cuts and fade-ins, panning from person to person, violent act/sound to violent act/explosion. In all four poems of his feature, there is the sky, which in this poem, “drops” and in others is the place into which people fly as “doomed birds.” In “Sugar, Sex and Zig-Zags,” the speaker dangles his legs from the clouds and soon after, he is flailing “into the ravine.” Louis’s poems and the pieces from the group show, LOG BOOK, “dedicated to the 60th anniversary of the first manned flight into space” that Visual Arts Co-Editor, Arlyce Menzies and I selected for this conversation speak to one another in their movements between planes. Even if the curator of the group show, Aigul Ibrayeva, orients the viewer’s gaze from the point of view of imaginary astronauts looking back towards the earth, in yearning and for guidance, and Louis’s poems stay home in the vortex of earthbound ecstasy, both Ibrayeva as the curator and the poet Corbin Louis press us to ask: What artifacts will /do subjects leave behind/what detritus? How will they grasp what they find: a nation’s artifacts or personal collections of unreadable objects?

On her Facebook page, Ibrayeva writes:

The theme of space in art is quite popular and lies on the surface! However, it is not all that simple! For more than half a century, the theme of space has represented a vast field for exploitation in art—in cinema, literature, music, in the sports and fashion industry, and in computer games. In the subcortex of the memory of most “Soviet” people, images of Gagarin and fragments of black-and-white documentaries emerge. For others, it's images of Hollywood characters from “Star Wars,” aliens, predators, and many other heroes.

In November of this past year, Poetry Editor, Theadora Siranian, and I were invited to the group show opening for LOG BOOK at Platforma Project-room at the last minute. Several times removed as the intended subjects, our sub-cortexes are not filled with “the memory of most ‘Soviet’ people” by the stories of the artifacts and landscapes. The invitees of an invitee, late for the catering (all that remains are traces of dumplings and tea), we pass by portraits of Genghis Khan in which he is flanked by gasoline canisters. Peter Aerschmann’s video of a chicken carcass as the floating axis around which batteries and plastic containers rotate is projected on a wall. Dima Virge’s eyeball sculptures that hang from the ceiling in several places in the gallery suggest that the installation revolves around us more than we around it.

At the main entrance to the exhibit is an installation by Askhat Akhmediyarov of several weathered suitcases packed with personal and not-so personal memento mori: a game board, a large pickling jar of yellow liquid, a Jedi sword, old Polaroids torn from family albums tacked to the wall. Above the Polaroids are Aidana Kulakhmetova’s works of yurt-hovercrafts soaring over collaged photographs of covid-masked tourists and families ambling in the Steppe. Throughout the exhibit, someone or thing is seeing from above and someone or thing is being seen on the ground.

The spatial dynamic in these collages recurs in Said Atabekov’s photo-series. In Atabekov’s photos, the hovering astronauts are subjects only insofar as the viewer presumes that they can see. Heads pointed away from the camera or clouds reflected in helmets keep the viewer from seeing them seeing.

The Battle of Qazygurt, Shymkent, 2021: N-8 Photograph (Series) by Said Atabekov

Static in space suits, the astronauts are staged in a face-off against the intense physicality of the horses and people on the ground. Ibrayeva describes Atabekov’s “Battle of Qazygurt” photo-series as “a sketch of a story about nomads who knew a lot about the stars in infinite space where there is no beginning and no visible end, and so wandered to other galaxies..... And after, they just lost their way in the Great Steppe.” The astronaut’s head is pointed at the humans and horses on the ground looking to the nomads for direction as if they were constellations. In another photo in the series, a parking lot just beyond frames the oppositions of nomad and astronaut as a scenario staged for someone else’s eye.

In Saule Dyussenbina’s oil painting, “Dumplings Keep Their Distance," a dozen or so evenly-spaced pelmeni float on the dark background, synthesizing the “ordinary” life of our last two years of consuming comfort food in isolation. In her portrait, she anthropomorphizes dumplings, staging a face-off between meal and eater, in which the directness of the “gaze” of the former suggests they are winning.

Dumplings Keep Their Distance, 2020: oils by Saule Dyussenbina

According to Ibrayeva, this canvas is part of a “continuation of the graphic series, ‘Dumplings,’ where dumplings are identified with people, and have topical conversations among themselves. Keeping their distance at a meter and a half during the pandemic, they hover above the table in dark space, surrounded by the white dust of galaxies! How this will end is unclear—perhaps they will fly on, in search of uncharted worlds, or maybe they will find themselves in a pot and be eaten—only time will tell.” Dyussenbina twists the commonplace admonition that we are what we eat into what we eat becomes us.

Towards the end of the exhibit, Abylai Murashbekov’s “Subjects in Space” is a group of bodies likewise together and separate. They appear to be holding human shape thanks to the ash of some fire that consumed their flesh. In the vitrine behind them, a ghostly furniture store continues to defiantly operate.

Subjects in Space, 2021: plastics, paper, and wire by Abylai Murashbekov

Murashbekov’s figures with their blank or mournful expressions, seem to be products of irony. In classical postures, stretching or bending over, they are barely differentiated from the ground and materials from which they emerge or the volcano of inescapable plastics into which they cannot fully disintegrate. Made of the discards of the everyday, Murashbekov’s recent figures live and burn in accumulated objects.

The three artists from LOG BOOK who are featured in this conversation of Angime play with positioning and re-positioning of the earth in relation to the universe; centering the fate of both or either in their practices of art-making. In making the subject of her portrait the repeating patterns of a staple of comfort foods, Dyussenbina, too, centers our focus on what is/what exists. She creates visual puns of the “meat and potatoes” (or pelmeni) of living. In Atabekov’s photo-series, he poses the “others” (astronaut-explorers, outsiders) to look at earth’s inhabitants (who couldn’t care less about astronauts) for meaning.

The world in Louis’s poetry is also composed of language-material, of the detritus of this “shining blue marble,” where nothing fully disintegrates: not words, nor material, where: It pays to deny 9 to 5 / It pays to avoid your ‘responsibilities’ / for bigger responsibilities like reading poems / Picking flowers and painting three thousand black circles in a row.